One of the many things COVID-19 has had a dramatic impact on is the way many of us work.

Those fortunate enough to be able to work from home have been able to adapt to this new reality – and it certainly has been “new”.

Perhaps the biggest question for both employers and employees is whether working from home has led to a decrease in productivity.

The fact major companies such as Facebook and Twitter have said they will allow many employees to work from home permanently suggests work in some sectors can be done more efficiently outside a formal workplace.

At a minimum, time saved from commuting and greater flexibility to multitask other elements of one’s life are positives from working from home.

Lack of social interaction and the inevitable distractions in most home environments are negatives.

The degree and extent of increased productivity from working at home remains to be seen.

It will depend on the way in which working in a team has evolved in a remote environment using online tools like Slack and Zoom.

The big question is how the nature of collaboration has changed under COVID.

Studying 3 million people

Thanks to a fascinating analysis by researchers from the Harvard Business School and New York University, we are beginning to get the first systematic evidence on how the nature of work has changed for those working from home during COVID-19.

The authors gathered aggregated meeting and email meta-data for 3,143,270 people working for 21,478 companies in 16 cities in Europe, the United States and Israel where government-mandated lockdowns were imposed in March.

As the authors put it:

These lockdowns established a clear break point after which we could infer that people were working from home. The earliest lockdown in our data occurred on March 8, 2020, in Milan, Italy, and the latest lockdown occurred on March 25, 2020, in Washington, DC.

To explore changes in worker behaviour, their analysis compares meeting and email data during the lockdown periods (typically a month long) with data for the eight weeks prior and the eight weeks after lockdowns ended.

The data they used came from “an information technology services provider that licenses digital communications solutions to organisations around the world”.

This meta-data indicates the actual behaviour of employees in real organisations.

So it’s more robust than, say, a survey asking people what they did. Survey respondents might not remember accurately, or might not tell the truth, and those that respond may not be a representative sample.

In short, the meta-data enables the authors to draw detailed and interesting conclusions that survey data would allow.

It’s the detail of a paper like this that is, in a sense, the whole point.

But the bottom line is this.

Lockdowns have reduced the amount of time most workers spend in meetings, but increased their working hours.

Time in meetings

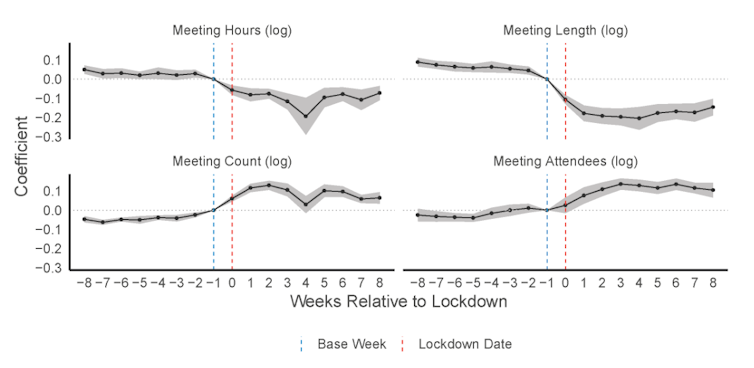

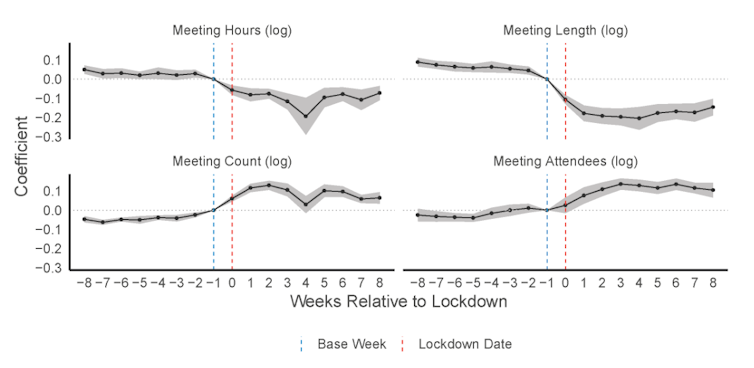

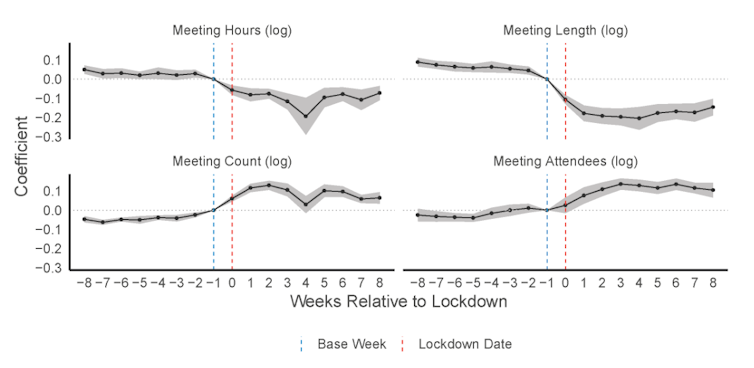

Their results show the number of meetings attended by workers increased, on average, by 12.9% during lockdown – with the average number of attendees per meeting increasing by 13.5%.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on meetings

But the average length of meetings fell by 20.1%, with the net effect being that people spent 11.5% less time in meetings.

In European cities such as Brussels, Oslo and Zurich, meeting length declined sharply and continued to fall in the month after the beginning of the lockdown.

In the US cities of Chicago, New York and Washington DC, length of meetings declined less.

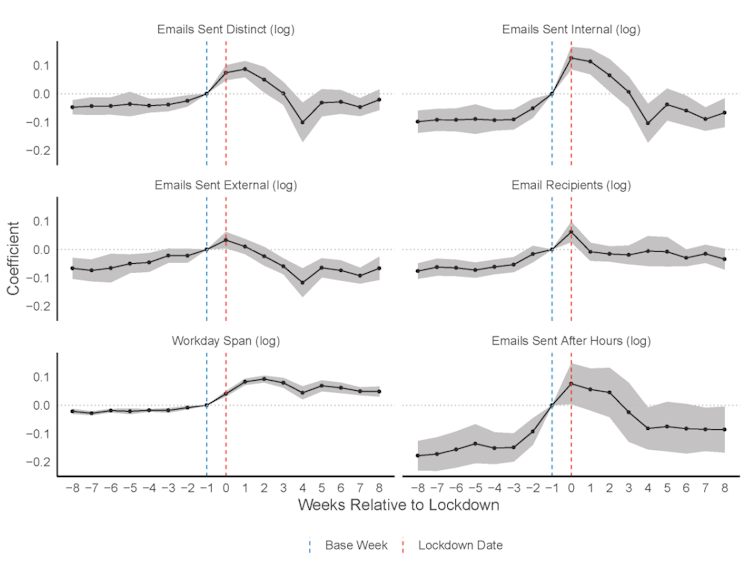

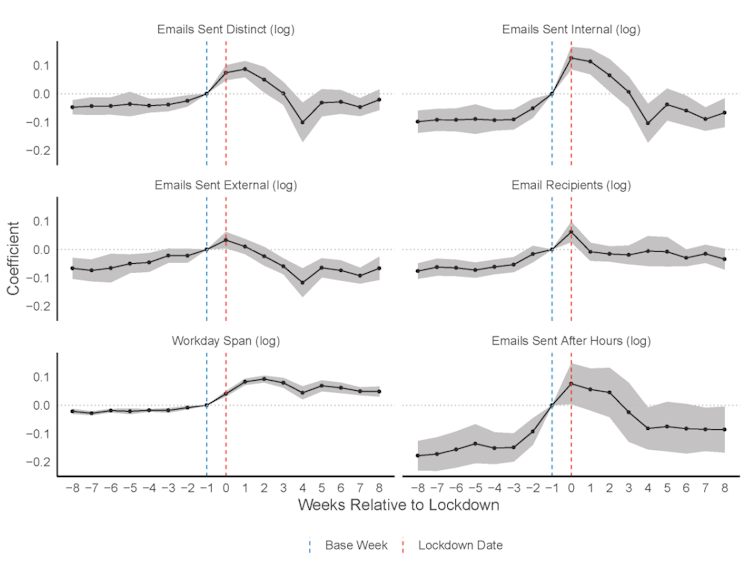

Email and working hours

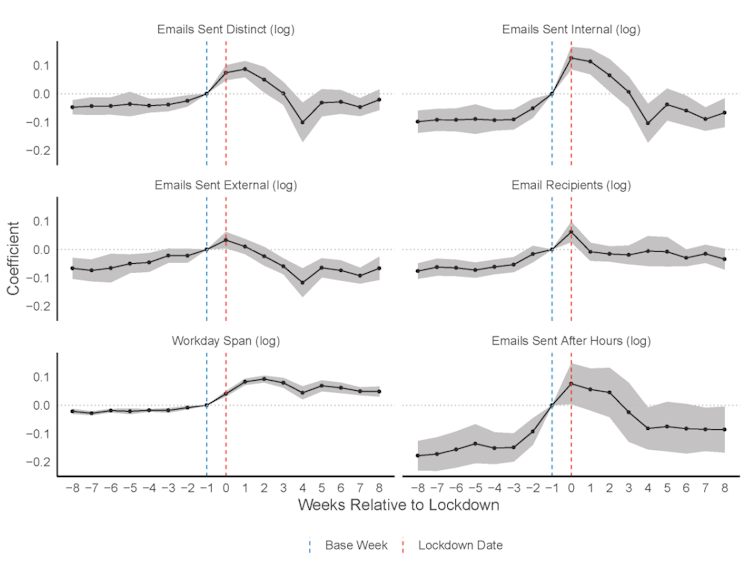

There was, also, a significant and seemingly durable increase in working hours, based on the number of hours between the first and last email sent or meeting attended by an individual in a day.

On average, the length of the average workday increased by 48.5 minutes.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on email

Longer workdays were common across the 16 cities during lockdowns.

When restrictions were lifted, average hours returned closer to pre-lockdown levels in all but three cities – San Jose, Rome and New York City.

The evolving nature of work

It is perhaps too early to draw strong conclusions about these changing patterns of communication. But there are some intriguing possibilities.

Larger meetings may be needed to get “everyone on the same page” and create what economists call “common knowledge”.

This may be both easier to do in phone or video conferences, and also more important in the absence of face-to-face communication.

Consistent with this, electronic communications extending beyond normal work hours seems like an inevitable consequence, albeit a negative one for work-life balance, particularly for people with caring responsibilities.

The nature of work was evolving before COVID-19, and it will continue to do so as many parts of the world continue with various forms of physical distancing.

Documenting the nature of that evolution, as well as the implications for productivity, workplace culture, and time outside of work will continue to be informed by remarkable data of the kind the authors analysed.

Richard Holden